Tic Tac Toe: Understanding the Minimax Algorithm

Note! This article is has also been translated to Japanese, Portuguese, and Russian. I really appreciate the readers that reached out to me and translated this article.

I recently built an unbeatable game of tic tac toe. It was a fun and very humbling project that taught me a ton. If you want to get totally schooled, give the tic tac toe game a shot here.

In order to make the game unbeatable, it was necessary to create an algorithm that could calculate all the possible moves available for the computer player and use some metric to determine the best possible move. After extensive research it became clear that the Minimax algorithm was right for the job.

It took a little while to really fundamentally understand the algorithm and implement it in my game. I found many code examples and explanations, but none that really walked a simpleton like me through the ins and outs of the process. I hope this post will help some of you to appreciate the elegance of this algorithm.

Describing a Perfect Game of Tic Tac Toe

To begin, let's start by defining what it means to play a perfect game of tic tac toe:

If I play perfectly, every time I play I will either win the game, or I will draw the game. Furthermore if I play against another perfect player, I will always draw the game.

How might we describe these situations quantitatively? Let's assign a score to the "end game conditions:"

- I win, hurray! I get 10 points!

- I lose, shit. I lose 10 points (because the other player gets 10 points)

- I draw, whatever. I get zero points, nobody gets any points.

So now we have a situation where we can determine a possible score for any game end state.

Looking at a Brief Example

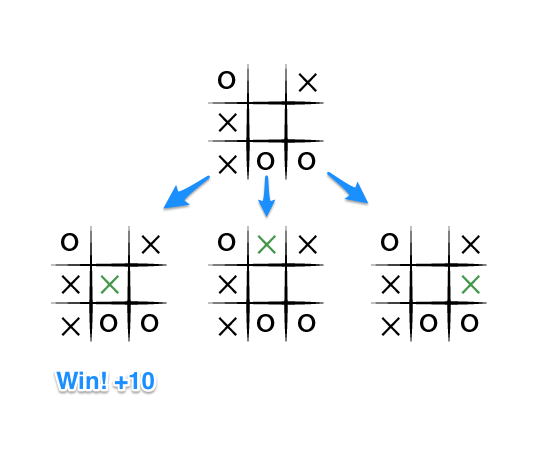

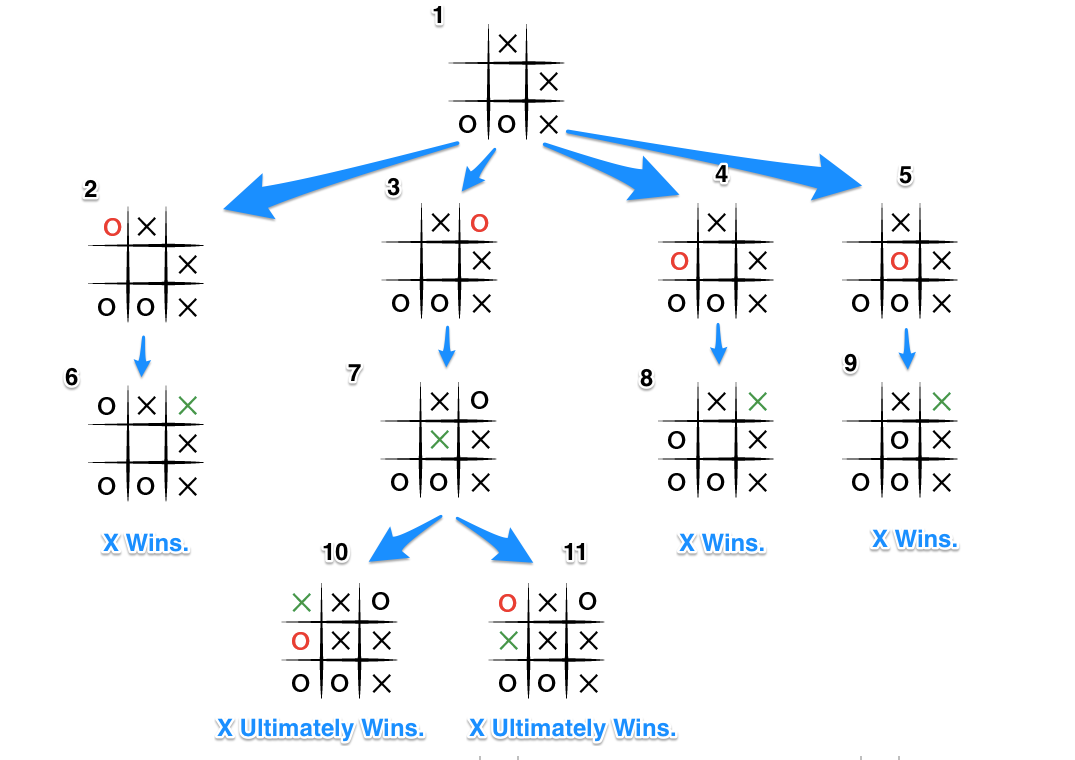

To apply this, let's take an example from near the end of a game, where it is my turn. I am X. My goal here, obviously, is to maximize my end game score.

If the top of this image represents the state of the game I see when it is my turn, then I have some choices to make, there are three places I can play, one of which clearly results in me wining and earning the 10 points. If I don't make that move, O could very easily win. And I don't want O to win, so my goal here, as the first player, should be to pick the maximum scoring move.

But What About O?

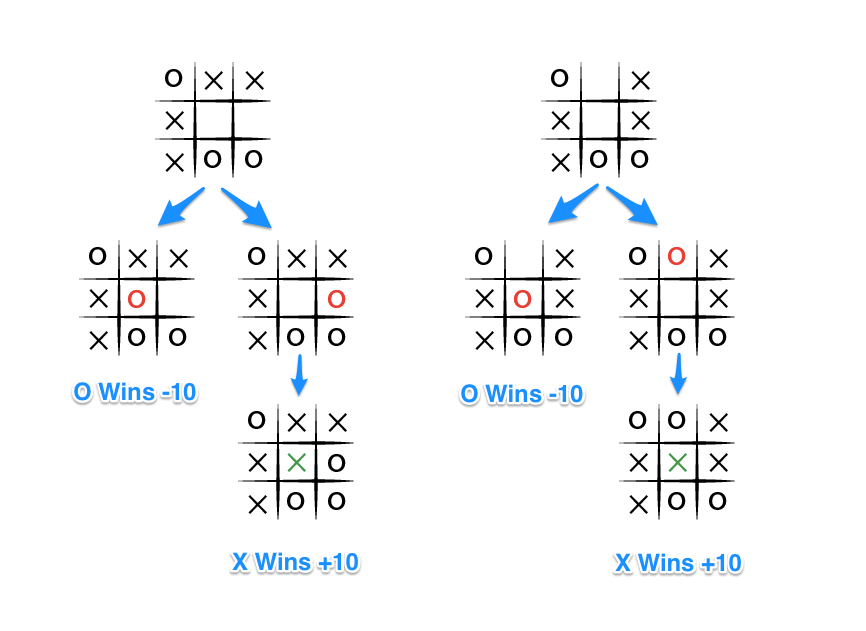

What do we know about O? Well we should assume that O is also playing to win this game, but relative to us, the first player, O wants obviously wants to chose the move that results in the worst score for us, it wants to pick a move that would minimize our ultimate score. Let's look at things from O's perspective, starting with the two other game states from above in which we don't immediately win:

The choice is clear, O would pick any of the moves that result in a score of -10.

Describing Minimax

The key to the Minimax algorithm is a back and forth between the two players, where the player whose "turn it is" desires to pick the move with the maximum score. In turn, the scores for each of the available moves are determined by the opposing player deciding which of its available moves has the minimum score. And the scores for the opposing players moves are again determined by the turn-taking player trying to maximize its score and so on all the way down the move tree to an end state.

A description for the algorithm, assuming X is the "turn taking player," would look something like:

- If the game is over, return the score from X's perspective.

- Otherwise get a list of new game states for every possible move

- Create a scores list

- For each of these states add the minimax result of that state to the scores list

- If it's X's turn, return the maximum score from the scores list

- If it's O's turn, return the minimum score from the scores list

You'll notice that this algorithm is recursive, it flips back and forth between the players until a final score is found.

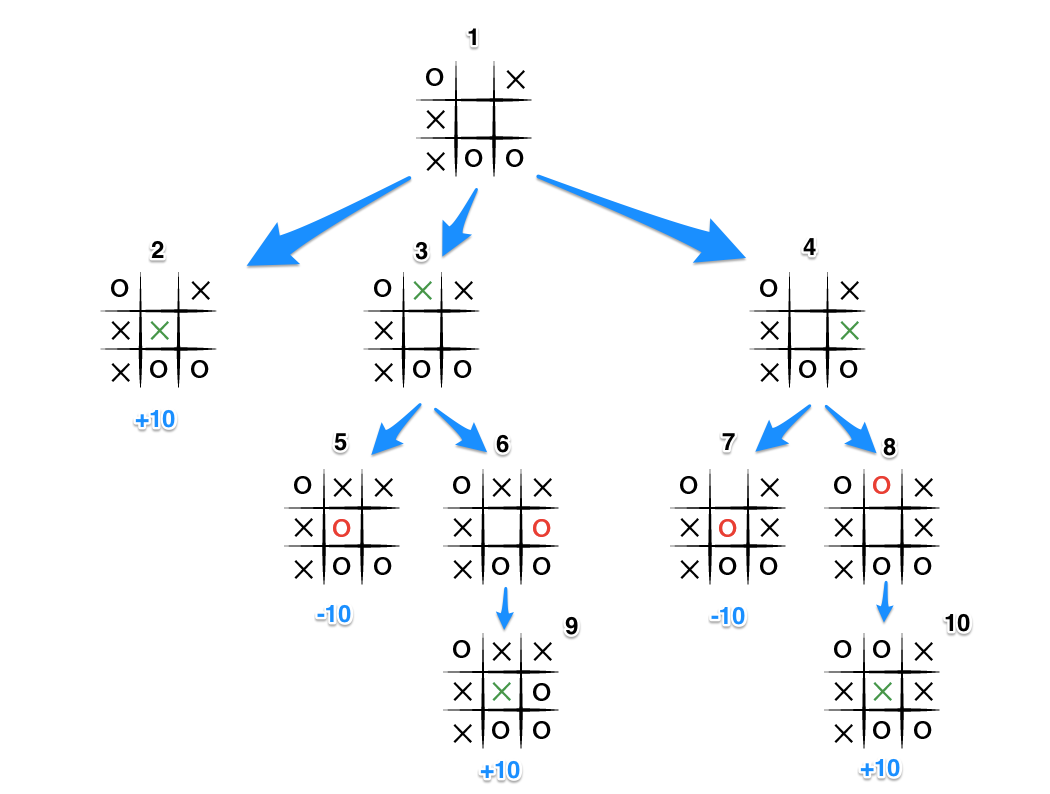

Let's walk through the algorithm's execution with the full move tree, and show why, algorithmically, the instant winning move will be picked:

- It's X's turn in state 1. X generates the states 2, 3, and 4 and calls minimax on those states.

- State 2 pushes the score of +10 to state 1's score list, because the game is in an end state.

- State 3 and 4 are not in end states, so 3 generates states 5 and 6 and calls minimax on them, while state 4 generates states 7 and 8 and calls minimax on them.

- State 5 pushes a score of -10 onto state 3's score list, while the same happens for state 7 which pushes a score of -10 onto state 4's score list.

- State 6 and 8 generate the only available moves, which are end states, and so both of them add the score of +10 to the move lists of states 3 and 4.

- Because it is O's turn in both state 3 and 4, O will seek to find the minimum score, and given the choice between -10 and +10, both states 3 and 4 will yield -10.

- Finally the score list for states 2, 3, and 4 are populated with +10, -10 and -10 respectively, and state 1 seeking to maximize the score will chose the winning move with score +10, state 2.

That is certainly a lot to take in. And that is why we have a computer execute this algorithm.

##A Coded Version of Minimax Hopefully by now you have a rough sense of how th e minimax algorithm determines the best move to play. Let's examine my implementation of the algorithm to solidify the understanding:

Here is the function for scoring the game:

# @player is the turn taking player

def score(game)

if game.win?(@player)

return 10

elsif game.win?(@opponent)

return -10

else

return 0

end

endSimple enough, return +10 if the current player wins the game, -10 if the other player wins and 0 for a draw. You will note that who the player is doesn't matter. X or O is irrelevant, only who's turn it happens to be.

And now the actual minimax algorithm; note that in this implementation a choice or move is simply a row / column address on the board, for example [0,2] is the top right square on a 3x3 board.

def minimax(game)

return score(game) if game.over?

scores = [] # an array of scores

moves = [] # an array of moves

# Populate the scores array, recursing as needed

game.get_available_moves.each do |move|

possible_game = game.get_new_state(move)

scores.push minimax(possible_game)

moves.push move

end

# Do the min or the max calculation

if game.active_turn == @player

# This is the max calculation

max_score_index = scores.each_with_index.max[1]

@choice = moves[max_score_index]

return scores[max_score_index]

else

# This is the min calculation

min_score_index = scores.each_with_index.min[1]

@choice = moves[min_score_index]

return scores[min_score_index]

end

endWhen this algorithm is run inside a PerfectPlayer class, the ultimate choice of best move is stored in the @choice variable, which is then used to return the new game state in which the current player has moved.

##A Perfect but Fatalist Player Implementing the above algorithm will get you to a point where your tic tac toe game can't be beat. But and interesting nuance that I discovered while testing is that a perfect player must always be perfect. In other words, in a situation where the perfect player eventually will lose or draw, the decisions on the next move are rather fatalistic. The algorithm essentially says: "hey I'm gonna lose anyway, so it really doesn't matter if I lose in the next more or 6 moves from now."

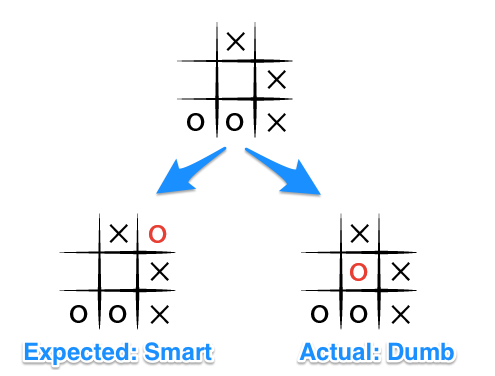

I discovered this by passing an obviously rigged board, or one with a "mistake" in it to the algorithm and asked for the next best move. I would have expected the perfect player to at least put up a fight and block my immediate win. It however, did not:

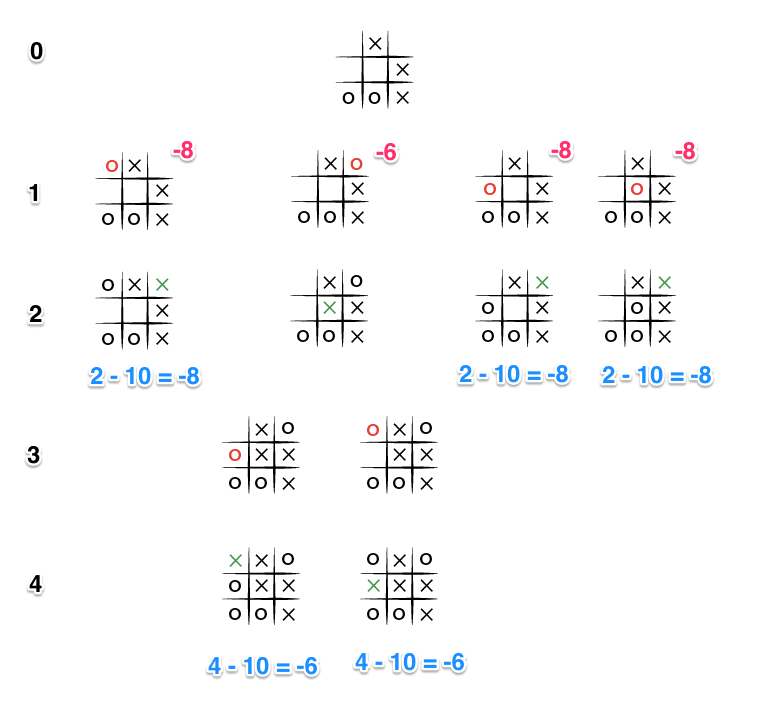

Let's see what is happening here by looking through the possible move tree (Note, I've removed some of the possible states for clarity):

- Given the board state 1 where both players are playing perfectly, and O is the computer player. O choses the move in state 5 and then immediately loses when X wins in state 9.

- But if O blocks X's win as in state 3, X will obviously block O's potential win as shown in state 7.

- This puts two certain wins for X as shown in state 10 and 11, so no matter which move O picks in state 7, X will ultimately win.

As a result of these scenarios, and the fact that we are iterating through each blank space, from left to right, top to bottom, all moves being equal, that is, resulting in a lose for O, the last move will be chosen as shown in state 5, as it is the last of the available moves in state 1. The array of moves being: [top-left, top-right, middle-left, middle-center].

What is a gosh-darn, tic tac toe master to do?

Fighting the Good Fight: Depth

The key improvement to this algorithm, such that, no matter the board arrangement, the perfect player will play perfectly unto its demise, is to take the "depth" or number of turns till the end of the game into account. Basically the perfect player should play perfectly, but prolong the game as much as possible.

In order to achieve this we will subtract the depth, that is the number of turns, or recursions, from the end game score, the more turns the lower the score, the fewer turns the higher the score. Updating our code from above we have something that looks like this:

def score(game, depth)

if game.win?(@player)

return 10 - depth

elsif game.win?(@opponent)

return depth - 10

else

return 0

end

end

def minimax(game, depth)

return score(game) if game.over?

depth += 1

scores = [] # an array of scores

moves = [] # an array of moves

# Populate the scores array, recursing as needed

game.get_available_moves.each do |move|

possible_game = game.get_new_state(move)

scores.push minimax(possible_game, depth)

moves.push move

end

# Do the min or the max calculation

if game.active_turn == @player

# This is the max calculation

max_score_index = scores.each_with_index.max[1]

@choice = moves[max_score_index]

return scores[max_score_index]

else

# This is the min calculation

min_score_index = scores.each_with_index.min[1]

@choice = moves[min_score_index]

return scores[min_score_index]

end

endSo each time we invoke minimax, depth is incremented by 1 and when the end game state is ultimately calculated, the score is adjusted by depth. Let's see how this looks in our move tree:

This time the depth (Shown in black on the left) causes the score to differ for each end state, and because the level 0 part of minimax will try to maximize the available scores (because O is the turn taking player), the -6 score will be chosen as it is greater than the other states with a score of -8. And so even faced with certain death, our trusty, perfect player now will chose the blocking move, rather than commit honor death.

In Conclusion

I hope all of this discussion has helped you further understand the minimax algorithm, and perhaps how to dominate at a game of tic tac toe. If you have further questions or anything is confusing, leave some comments and I'll try to improve the article. All of the source code for my tic tac toe game can be found on github.